|

Len Gabriels

Skyhooks Sailwing Company

Lens Gabriels Web-Site

|

Len Gabriels flying his Mk 1 at Lobden Moor in February 1973

This lead by steps to a Mk3 version that was later sold in plan form from about April the same year

|

Len model flying with his friends early 1970's

|

Graham Hobson flying one of Lens 2nd generation hang gliders the Coud 9 released in 1975

Len Gabriels flying his experimental Canard wing 25th December 1977

Len Gabriels

'Unknown Pioneer' By David BremnerLast month we announced that Skyhook Sailwings was closing down after 25 year’s trading in the hang gliding and microlighting business. Both are volatile businesses, and to be able to trade so long, and to close down without owing anyone a penny is probably a unique achievement. But those who started microlighting after 1984 may not be aware of the achievements of Skyhooks proprietor, Len Gabriels and so I went semi in Oldham to try to winkle out more details from this unassuming man. I asked him what had attracted his attention to hang gliding in the first place.

LG: ‘In 1972 I read an article in my children’s Look and Learn Magazine describing the exploits of the early American pioneers. There were no photographs, just a line drawing, but the interest grew from that. An article in the newspaper about Geoff McBrooms experiments with them in the Bristol area led me to try to contact him. For a long time I got no reply, and when eventually I did get in touch, I discovered this was because he’d broken his arm in a hang gliding accident – which was why he wasn’t prepared to sell me any plans.’

DB: ‘How old were you at this time?’

LG: ‘I was born in 1926, so that makes it… 46.’

DB: “and what was your background up to that time?’

LG: ‘I was a time served toolmaker, and in the early 1950’s was asked to join a new engineering company, Frastan, being set up by a wallpaper manufacturer to serve their engineering needs. I was asked to design a machine for making the rolls of wallpaper, and this product became the basis of the engineering company’s expansion until now they are sold all over the world. At the time I started hang gliding I was engineering director, and I have been managing director for many years.

DB: ‘But this doesn’t explain your interest in aviation?’

LG: ‘I had always been interested in model flying, and was a member of the local club. I had even made my own 0.4cc diesel engines which I used to power a scale model of a Miles Gemini light twin. Some (one) of my model designs are (is) still being sold.

DB: ‘So how did you go about making a hang glider without plans?’

LG; ‘I established the basic layout using small models made from balsa and plastic sheet, then scaled it up. The fabric was sewn on my wife’s sewing machine, and I ruined the kitchen floor by hammering fittings into the ends of the spars. We found that it required a VERY steep hill to get airborne, and that it was far too big (the leading edges were 24ft long!). The third design was successful, and became the Skyhook 3A. I advertised the plans in Aeromodeller magazines, and we sold 2,500 copies. This generated a huge number of enquiries about where to get the tube, fabric, etc, so it seemed a good idea to sell kits, and eventually completed hang gliders.’

DB: ‘I remembered even then that Len Gabriels was regarded with awe for his flying skills. Did you hold any records?’

LG: ‘I think I held the duration record of 28 minutes (on Pendle Hill) for a few weeks, but that was all.’

DB: ‘I know you had always thought that hang gliders could be motorized. How did you get started down this route?’

LG: ‘When people started trying out the Soarmaster units, I came up with the Rowena 110cc which was used on very large model aircraft. They weren’t powerful enough on their own, so I used two, one each side of the uprights (See photograph). This worked okay, but the propellers were very small, noisy and inefficient.’

DB: ‘You crossed the channel in a powered hang glider, didn’t you? How did this come about?’

LG: ‘In 1979 I was asked by Brian Milton to develop a unit fat a flight from London to Paris sponsored by Bluebird toffees. This was a Safari single surface wing powered by a 123cc McCullough 101 engine, with the propeller mounted at the back of the keel. All went well, and Brian and I went to Mere in Wiltshire for a final try out. Unfortunately Brian stalled. The very high thrust line meant that it slowly rotated past the vertical, Brian fell into the inverted sail, and the tips broke upwards. It was an inherent problem with this configuration. Happily Brian landed on soft earth, and suffered no more than a broken arm, but the incident was being filmed by the BBC and was subsequently broadcast nationwide.

None the less, Bluebirds were still keen to go ahead, and so I was asked to make the next attempt. It had a duration of 2 ¼ hours, which at say 25mph didn’t give us a huge range. Starting from Potters Bar, I made it to Dover on the first leg, refueled, and then got airborne again. I had to wait at the coast until I see Brian and the rest of the crew embark on the ferry, and I set off with them. The flight across the channel was uneventful, and I climbed all the way. My jaw got tired from gripping the throttle for so long, but I landed without problems. We had been assured by the CAA that the French had a positive attitude to aviation and that there would be no problem, but in fact there were considerable delays since they did not know how to classify us. In the middle of the negotiations, news came through of Lord Mountbatten’s murder, and it became clear that even if we completed the trip, there would be no news coverage. We carried on as far as Abbeville, where the gendarmes indicated that although they couldn’t find anything illegal to charge us with they were quite happy to keep us for questioning until we decided to go home… and that, in the circumstances, seemed the most sensible thing to do.’

DB: ‘You then started making trikes didn’t you?. The one people remember is the twin engine one. How did that come about?’

LG: ‘I wanted a two seater to train people on. At that time there was no reliable unit been successfully using the Rowena Solo 210 engine on single seaters and adapted an idea I’d seen non an American paratrike unit of mounting two engines side by side, one facing forwards, the other backwards. They had belt drives on to concentric prop shafts in the middle, so that the props were contra-rotating. This gave me adequate power two up and more than adequate flown solo. I only built a few, one of which was adapted for hands-only controls for David Tye, who is a paraplegic.’

DB; ‘Do you claim to have invented any features of flexwings or trikes in use today?’

LG; ’Most ideas occurred by a process of gradual development rather than blinding inspiration by an individual. I think I was the first to use pre-formed battens in a wing’

DB. ‘But I know you always had a penchant for trying out new ideas. Tell me about some of them.’

LG. ‘Well, there was a bowsprit design like the Striker, but instead of reflexed tail feathers it had a small canard rigged between the bowsprit and the front wires. It certainly gave very positive pitch stability, but the performance was disappointing.’

BD; ‘And I remember getting very excited about the footlaunched enclosed canard you had at one time.’

LG. ‘Yes, model tests were very encouraging, and the full size one was capable of being folded down foe rooftop transport. But trials on Pilling sands were not encouraging, so no further work was done on it.’

DB; ‘For some time now, Skyhook has concentrated almost entirely on making Flash wings (sails) for Mainair. How did that come about?’

LG; ‘We had always been a small outfit, and the onset of regulation of microlights in 1984 would have meant a huge and unjustifiable investment. About this time John Hudson of Mainair was looking for someone to manufacture sails for their first in-house wing, the Flash, and contacted me. It was something of a godsend, as skyhook was in the red, and I didn’t want to go bankrupt, as it might have affected my position as engineering director of Franstan. From a financial point of view, it was a wise decision; it has given Skyhook a security it never had before. At the peak, we were turning out 26 wings (sails) a month; we have made nearly 900 Flash and blade wings (sail) in total, and not one manufacturing defect has been reported. We have been asked to make the odd hang glider since then, but we haven’t advertised.’

DB; ‘So why did you decide to call it a day?’

LG; ‘Franstan’s required me to undergo a very thorough annual medical. One of these indicated a possible heart problem, and so I had to stop flying. By the time I had had further checks which gave me the all clear, I had lost a year’s flying. By then, I had developed an interest in dinghy sailing, and felt out of touch with the flying fraternity. Mainair have bought all the machinery and jigs, and my employees, the two Margarets, are working for them in Rochdale. The transition has happened with the minimum of fuss, and no-one is owed a penny.’

DB; ‘And what of the future?’

LG; ‘I currently work three days a week at Franstan, but I am looking shortly to be able to finish there altogether. I shall be able to enjoy sailing if the reservoir ever fills up again. As far as flying is concerned, I feel privileged to have been involved during the most exciting period of its development, and I have no regrets about moving on to other things.’

I left Len with a profound respect for a man who had worked his way up from toolmaker to managing director, and in his spare time had developed and learned how to fly one of the first commercially available hang glider in the UK. Run one of the major manufacturers in the business for 23 years, and finally brought it to a satisfactory conclusion. To those of you who in their mid forties thought yourselves very adventurous by taking up microlighting in designs that are thoroughly tried and tested, give a thought to Len, who learned how to design, make and fly one from scratch; in contrast to the other pioneers, he is a man who brought the craftsmanship and care of a toolmaker to the task of learning how to make and fly hang gliders and microlights.The red highlighter words are some of the corrections Len wanted changed, while the blue is Lens words

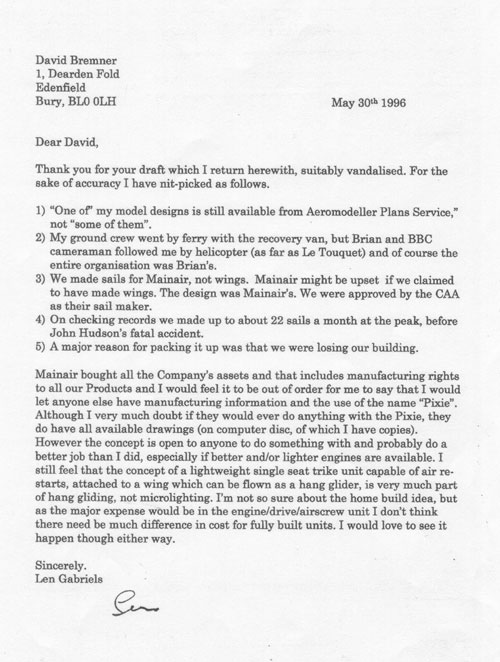

This is a copy of Lens reply to David

Len also wanted to mention that the ground crew for the Channel crossing consisted of Terry and Mark Silvester and Fred Walton

And when he left hang gliding he owed no money, got out on his terms and that he had personally test flown almost 90% of all the hang gliders he had built

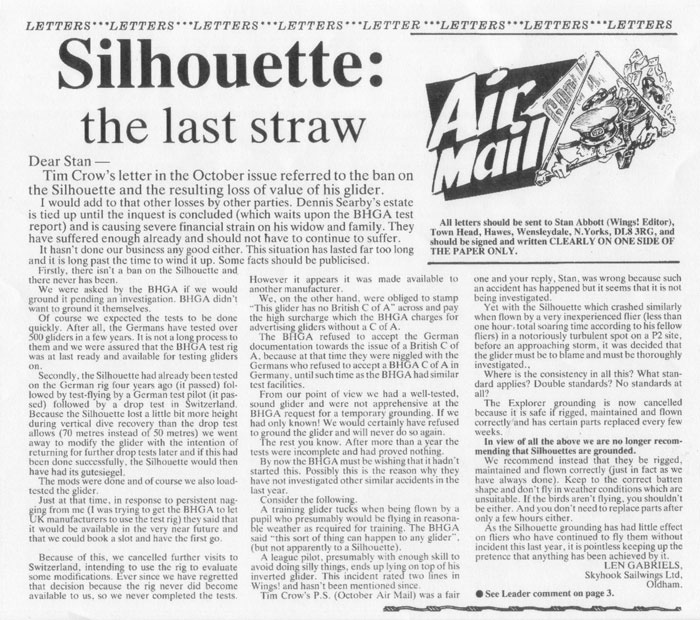

An article that Len sent the BHGA Wings magazine

All the material on this site is subject to copyright

Much of this material may only be reproduced with the written permission of the copyright holder